Preface

The mediator just announced Facebook's settlement plan: $65 million. The room fell silent. Mark Zuckerberg's lawyers waited for a response.

Most people would take the money and leave. Tyler Winklevoss looked at his brother Cameron Winklevoss, then across the table.

"We choose stocks."

The lawyers might have exchanged glances. Facebook was still a private company, and the stocks could be worthless, with the company potentially failing. Cash was tangible, while stocks were a bold gamble.

But Tyler's response would define the next decade of their lives. They bet the entire settlement on a company that had technically stolen their idea.

When Facebook went public in 2012, their $45 million in stocks were worth nearly $500 million.

The Winklevoss brothers had completed one of the boldest moves in Silicon Valley history. They lost the battle for Facebook but earned more money from Facebook than most early employees.

In 2013, they seized another opportunity.

Birth of a Mirror

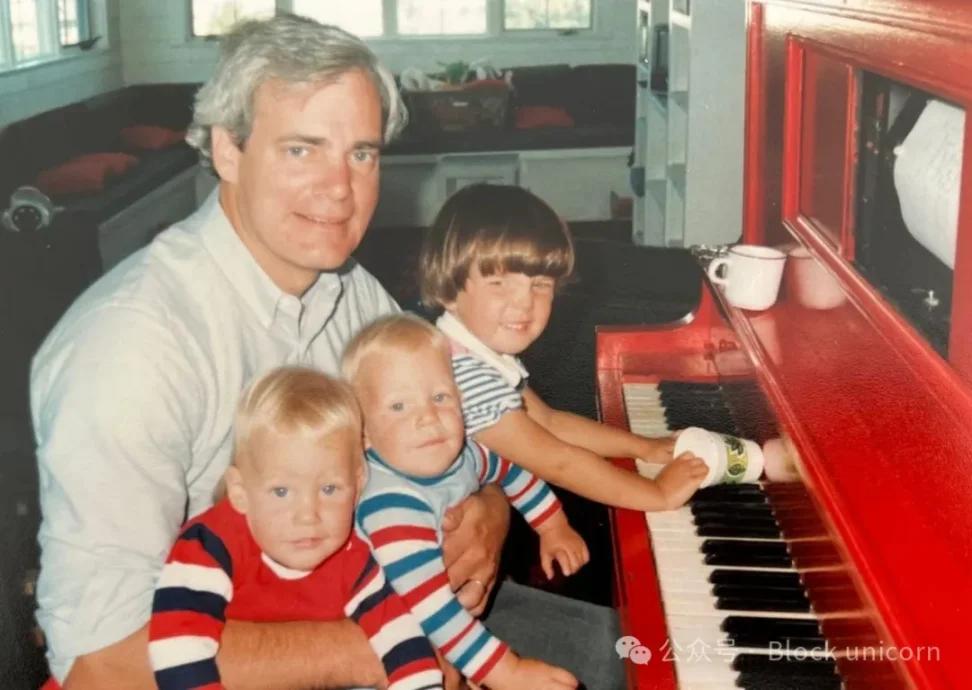

Before becoming crypto billionaires or Facebook lawsuit plaintiffs, Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss were each other's mirrors, literally.

Born on August 21, 1981, in Greenwich, Connecticut, they were identical twins with one key difference: Cameron was left-handed, Tyler was right-handed. Perfect symmetry.

They were tall, athletically gifted, and perfectly coordinated. At 13, they self-taught HTML and built websites for local businesses. During their teenage years, they created their first web company, building websites for any paying client.

At Greenwich Country Day School and later Brunswick School, they discovered competitive rowing and co-founded the school's rowing program.

In an eight-person boat, timing is crucial. A fraction of a second slower means losing. Perfect coordination requires understanding teammates, reading the water, and making split-second decisions under pressure.

They became exceptional. Exceptional enough to row at Harvard, exceptional enough to aim for the Olympics.

But rowing taught them something far more valuable than sporting honors—the art of perfect timing and seamless collaboration.

Harvard Laboratory

In 2000, the Winklevoss twins entered Harvard University, majoring in economics, with Olympic dreams.

Cameron joined the men's team, the exclusive Porcellian Club, and the Hasty Pudding Club. The brothers invested intensely in competitive rowing, a focus that ultimately took them to the international stage.

In 2004, they helped Harvard's team, nicknamed the "God Squad," achieve a perfect collegiate rowing season. They won the Eastern Sprint, the College Rowing Association Championship, and the legendary Harvard-Yale Boat Race.

But an important discovery happened off the water.

In December 2002, during their junior year, the twins conceived HarvardConnection, later renamed ConnectU, while studying the social dynamics of elite university life.

Their idea was to create an exclusive college social network, starting from Harvard and expanding to other elite universities. They deeply understood their generation's needs: students wanted to connect digitally, but existing tools were clumsy and uniform.

There was just one problem: they were athletes and economics majors, not programmers.

They needed help, needed a smart person who could understand their vision.

Then Mark Zuckerberg appeared.

October 2003, Kirkland Dining Hall at Harvard.

The twins presented their social network idea to Mark Zuckerberg. A sophomore computer science major, reportedly developing a project called Facemash where students could rate each other's photos.

Perfect.

They explained the HarvardConnection vision to Zuckerberg. He listened carefully, nodded, asked about features and technical details, seeming interested. They scheduled follow-up meetings.

For weeks, everything progressed smoothly. Zuckerberg participated in discussing the idea, explored implementation details, and appeared invested in the project. The twins thought they had found their programmer.

January 11, 2004. While waiting for their next meeting with Zuckerberg, he registered a domain: thefacebook.com.

Four days later, instead of meeting them, he launched Facebook.

The twins discovered this in the Harvard Crimson, realizing their programmer had become a competitor. They understood they had been deceived.

(Translation continues in the same manner for the rest of the text)Their friends must have thought they were crazy.

But they had witnessed a dorm room idea turn into a company worth billions of dollars. They understood how quickly the impossible could become inevitable.

Their analysis was: if Bit becomes a new type of currency, early adopters will gain huge returns; if it fails, they can afford the loss.

When Bit reached $20,000 in 2017, their $11 million turned into over $1 billion. They became the world's first confirmed Bit billionaires.

This pattern was gradually becoming clear. Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss had unique insights.

Building Infrastructure

The twins not only bought Bit and waited for appreciation, but they began to build infrastructure to drive mass adoption.

Winklevoss Capital provided seed funding for building a new digital economy: exchanges (like BitInstant), blockchain infrastructure, custody tools, analysis platforms, and later DeFi and Non-Fungible Token projects. Their investment portfolio covered everything from protocol developers (like Protocol Labs and Filecoin) to energy infrastructure for crypto mining.

In 2013, they submitted the first Bit ETF application to the SEC. This was an almost doomed attempt, but someone had to take the first step. In March 2017, the SEC rejected their application due to market manipulation. They tried again, and were rejected again in July 2018. But their regulatory efforts laid the groundwork for other applicants. In January 2024, spot Bit ETF was finally approved, marking the fruition of the framework this twin pair had begun building over a decade ago.

In 2014, BitInstant CEO Charlie Shrem was arrested at the airport for money laundering related to Silk Road transactions, and BitInstant was forced to close. The major Bit exchange Mt. Gox was hacked, losing 800,000 Bits. The infrastructure the twins invested in was collapsing, and the Bit market was turbulent.

But they saw opportunity in the chaos. The Bit ecosystem needed legal, regulated companies.

In 2014, they founded Gemini, one of the first regulated crypto exchanges in the US. While other crypto platforms operated in legal gray areas, Gemini collaborated with New York state regulators to establish a clear compliance framework.

They understood that for crypto to become mainstream, it needed institutional-level infrastructure. The New York State Department of Financial Services granted Gemini a limited purpose trust license, making it one of the first Bit exchanges licensed in the US.

By 2021, Gemini was valued at $7.1 billion, with the twins owning at least 75% of the shares. Today, the exchange has total assets over $10 billion, supporting more than 80 cryptocurrencies.

Through Winklevoss Capital, they invested in 23 crypto projects, including participating in Filecoin's funding round and Protocol Labs in 2017.

The Winklevoss brothers did not fight regulators, but instead worked to educate them. They did not seek regulatory arbitrage, but integrated compliance into their products from the beginning.

Gemini faced challenges including a $2.18 billion settlement agreement for its Earn program in 2024. But the exchange survived and continued operations.

The twins understood that technology alone was insufficient for success, and regulatory acceptance would determine the fate of cryptocurrency.

In 2024, they each donated $1 million in Bit to Donald Trump's presidential campaign, positioning themselves as advocates for crypto-friendly policies. Their donations exceeded federal contribution limits and partially needed to be returned, but they had made their stance clear.

The twin brothers have been outspoken in criticizing the SEC's overly aggressive enforcement under Chairman Gary Gensler. Their regulatory battles involve both personal and professional development. The SEC's lawsuit against Gemini directly challenged their business model. In June 2025, Gemini secretly filed an IPO.

Current Achievements

Forbes currently values the brothers at $4.4 billion, with a total net worth of about $9 billion, with Bit assets constituting the largest component of their wealth.

Their crypto assets include approximately 70,000 Bits worth $4.48 billion, along with substantial positions in Ethereum, Filecoin, and other digital assets.

Gemini remains one of the world's most trusted crypto exchanges, with institutional-level security features and regulatory compliance. The exchange's IPO application marks an important step towards integration with mainstream financial markets.

In February 2025, the twins became partial owners of Real Bedford, an eighth-tier English football club, investing $4.5 million.

Collaborating with crypto podcast host Peter McCormack, they are trying to push this semi-professional team towards the Premier League. Their father Howard also donated $4 million in Bit to Grove City College in 2024, the first Bit donation the school received, to fund the new Winklevoss Business School.

The twin brothers personally donated $10 million to Greenwich Country Day School, the largest alumni donation in the school's history.

They publicly stated that they would not sell Bit even if its market value reaches the level of gold, demonstrating their belief that Bit is not just a store of value, but a fundamental reimagining of currency.

The Harvard Crimson exposed Mark Zuckerberg's betrayal, and a one-dollar bill on an Ibiza beach ignited a revolution - these two moments occurred before and after they learned to see what others could not. Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss have long been considered as having missed the party. It turns out they just arrived early at the next feast.